Ask a Conservator: How Do You Handle Sensitive Materials?

From building microclimates to considering cultural backgrounds, here are a few ways conservators work to protect artworks.

Ask a Conservator is a regular series demystifying the work that conservators do at the Brooklyn Museum.

Conservators are often asked to work with art that is considered sensitive for one reason or another. Each object has its own issues due to size, age, materials, how it hangs or sits, its history before entering the Museum, and other considerations. Let’s break down a few of the primary categories.

Environment: Organic materials are generally sensitive to environmental factors such as relative humidity and light. Plant- and animal-based materials such as wood, ivory, and cotton absorb and desorb moisture from the air, which makes them expand and contract, causing stress and strain. They can also fade or become embrittled with exposure to light, especially UV light. We mitigate these issues by controlling the temperature and humidity fluctuation in the gallery and in storage, and by monitoring light levels and exposure.

Examples of light-sensitive materials include feathers, color photographs, and dyed textiles. Archaeological materials are often sensitive to fluctuations in humidity, which is a result of having been buried: elements from the soil interact with materials such as metals and glass and begin to break down the structure. Fluctuations in relative humidity exacerbate these issues and promote disintegration, so conservators create tightly controlled environments called microclimates to store and display them.

Microclimates are created with materials, such as desiccant and aluminum tape, that contain and control the interior environment of a small space. For example, microclimates can exist in display cases, storage boxes, and paintings’ frame packages. (Photo: Josh Summer)

Microclimates are created with materials, such as desiccant and aluminum tape, that contain and control the interior environment of a small space. For example, microclimates can exist in display cases, storage boxes, and paintings’ frame packages. (Photo: Josh Summer)

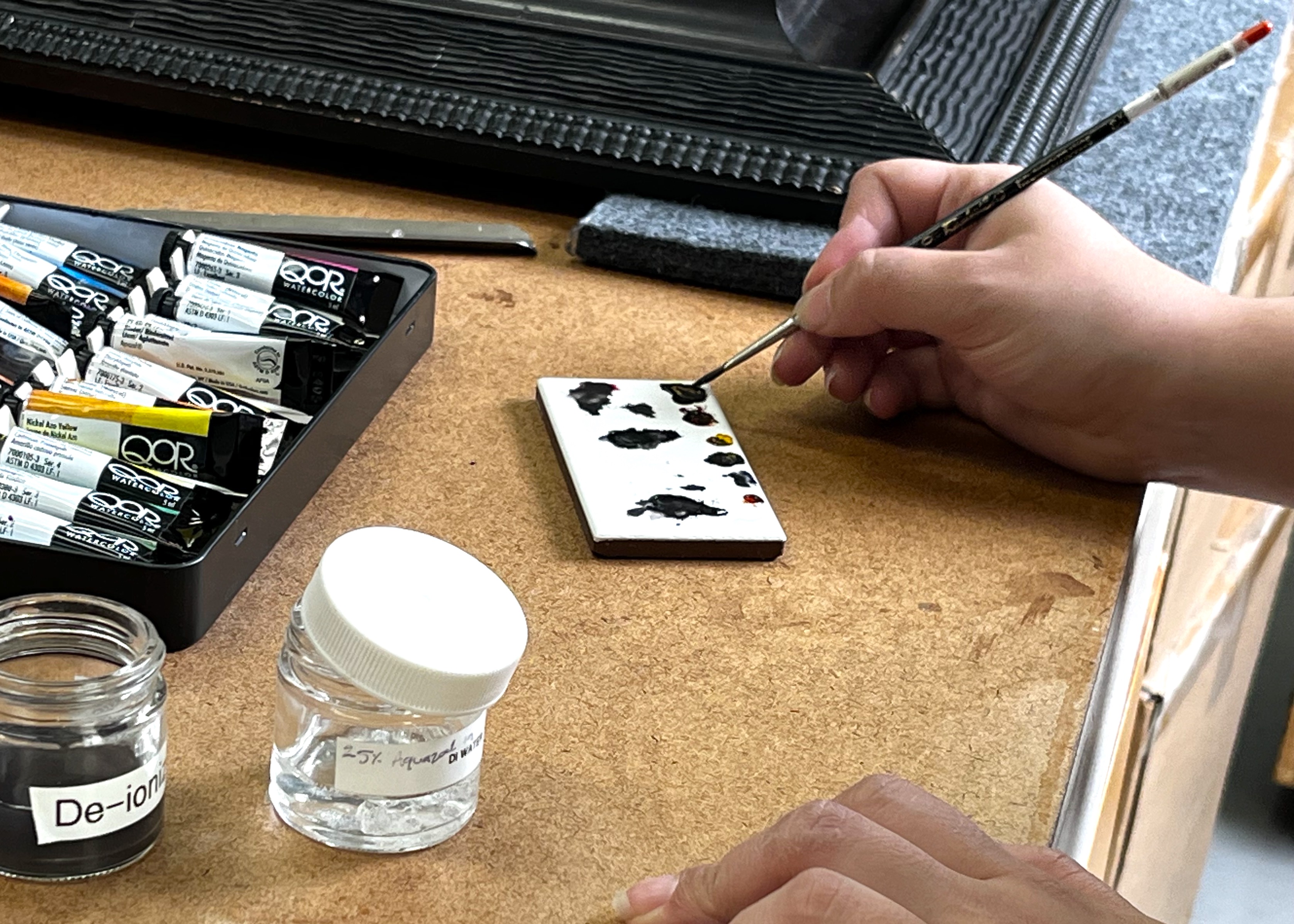

Handling: Some works have very sensitive surfaces that scratch easily or are more likely to corrode due to various factors, such as contact with oils from our skin. Examples of sensitive artworks include contemporary sculptures with mirrored or glossy finishes, face-mounted photos (where the printed side is affixed to a piece of plexi or glass), and photos on metal panels. We have specialized handling instructions that outline how and where to touch and lift such works, and we wear gloves at all times to avoid smudges or fingerprints.

When you are in the galleries, you may notice that many artworks are under a vitrine or framed. This is to protect them both from the public and from dust and dirt that would have to be regularly cleaned, thus increasing the wear on the object’s surface.

Cultural: Our collections include materials that are sensitive for cultural reasons. Some objects were intended to be seen or handled only by certain people, or used for sacred purposes. We also have collections that contain human remains, such as mummified individuals and reliquaries.

Preserving these objects begins with carefully researching what they are and how they came into the collections. This effort often involves building relationships with the relevant communities in order to fully understand their needs. We also clearly label these materials to indicate who should and should not handle them. How to care for culturally sensitive materials in museums is an evolving topic, and conservators are part of a team that is dedicated to establishing best practices and treating every work in our collection with the utmost consideration. Learn more on our provenance webpage.

Kate Wight Tyler is an Objects Conservator at the Brooklyn Museum.