Ask a Conservator: What’s the Weirdest Work You’ve Ever Conserved?

Introducing a new column that demystifies the work of museum conservators.

Ask a Conservator is a regular series demystifying the work that conservators do at the Brooklyn Museum. In this first edition, Carol Lee Shen Chief Conservator Lisa Bruno recalls one of her stranger projects and how its lessons inform her team's everyday work.

An adult blowfly that’s just hatched from its pupal state is the softest thing you’ll ever touch.

How do I know this? Live blowflies were an element in the 1990 sculptural installation A Thousand Years by the British contemporary artist Damien Hirst. Nine years later, the work appeared in the exhibition Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection at the Brooklyn Museum. The Conservation department—specifically, I—had to maintain this installation by replenishing the blowflies every week after they had completed their life cycle.

A blowfly has several life stages. It starts as an egg, then hatches into the larval stage, progressing to the pupal stage and finally emerging as an adult fly. Interestingly enough, there are non-art-related reasons a person might want to ship a container of blowfly larvae to their home, such as providing live feed for reptilian pets or (for fishing enthusiasts) to use as bait. While we could, in theory, buy the larvae, we wanted blowfly at the pupal stage.

The art conservator’s goal is to make sure the art is the truest it can be.

After thorough research and a couple of dry runs testing the shipping procedures and timing, we arranged to purchase larvae from a live-feed purveyor in Ohio. We’d have the company ship the larvae to us without their usual enclosure of dry ice, so that the transition from larva to pupa could happen while in transit. The pupae would then be placed into a glass case to hatch that week, where they would live out their life sustained by sugar water that had been dyed red to appear like blood.

It generally worked . . . until it didn’t.

Days before the opening, the very first shipment arrived—not according to the plan we had worked out, but instead on dry ice, as was customary for the company. I had to improvise: I very quickly learned how to push a blowfly’s transition from larval stage to pupal. We set up a nursery with gauze-covered trays of larvae, space heaters, and hot lamps in a supply storeroom and waited. It was a long weekend of expectation; luckily, by Monday, the writhing larvae had changed to inert pupae. The exhibition was opening later that week, giving us enough time to bring the pupae to the exhibition and have them hatch a few days later, just in time for the Member preview.

Managing live blowflies was an important part of the conservation team’s work on the Brooklyn Museum’s 1999 exhibition Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection. (Photo: Lisa Bruno)

It was magical to see the swarm of flies inside the exhibition case. The other shipments throughout the course of the exhibition arrived without incident except for one: that time, the autumn weather was hotter than usual, and there was a delay in delivery. When the box finally arrived, the pupae had already started to hatch.

A Thousand Years by Damien Hirst in the exhibition Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection, on view October 2, 1999–January 9, 2000. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

A Thousand Years by Damien Hirst in the exhibition Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection, on view October 2, 1999–January 9, 2000. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

I never—not in a million years—thought I’d have to work with live blowflies as an art conservator. Then again, art is made from anything and everything: traditional materials like oil paint, charcoal, stone, and metal, as well as less common materials like urine, blood, scent, and sound.

Carol Lee Shen Chief Conservator Lisa Bruno works with an object in the conservation lab at the Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Corinne Segal)

Carol Lee Shen Chief Conservator Lisa Bruno works with an object in the conservation lab at the Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Corinne Segal)

Art conservators are often faced with the challenge of identifying the materials used in a given object and figuring out how to manipulate them to preserve the artwork. They’re tasked, too, with looking at the way an object changes over time and determining how much of that change came from the process of making the art versus deterioration. If there is deterioration, then we must ask if it came from a natural decay process (known in the field as inherent vice) or if it was due to external forces such as light, water, or human interaction.

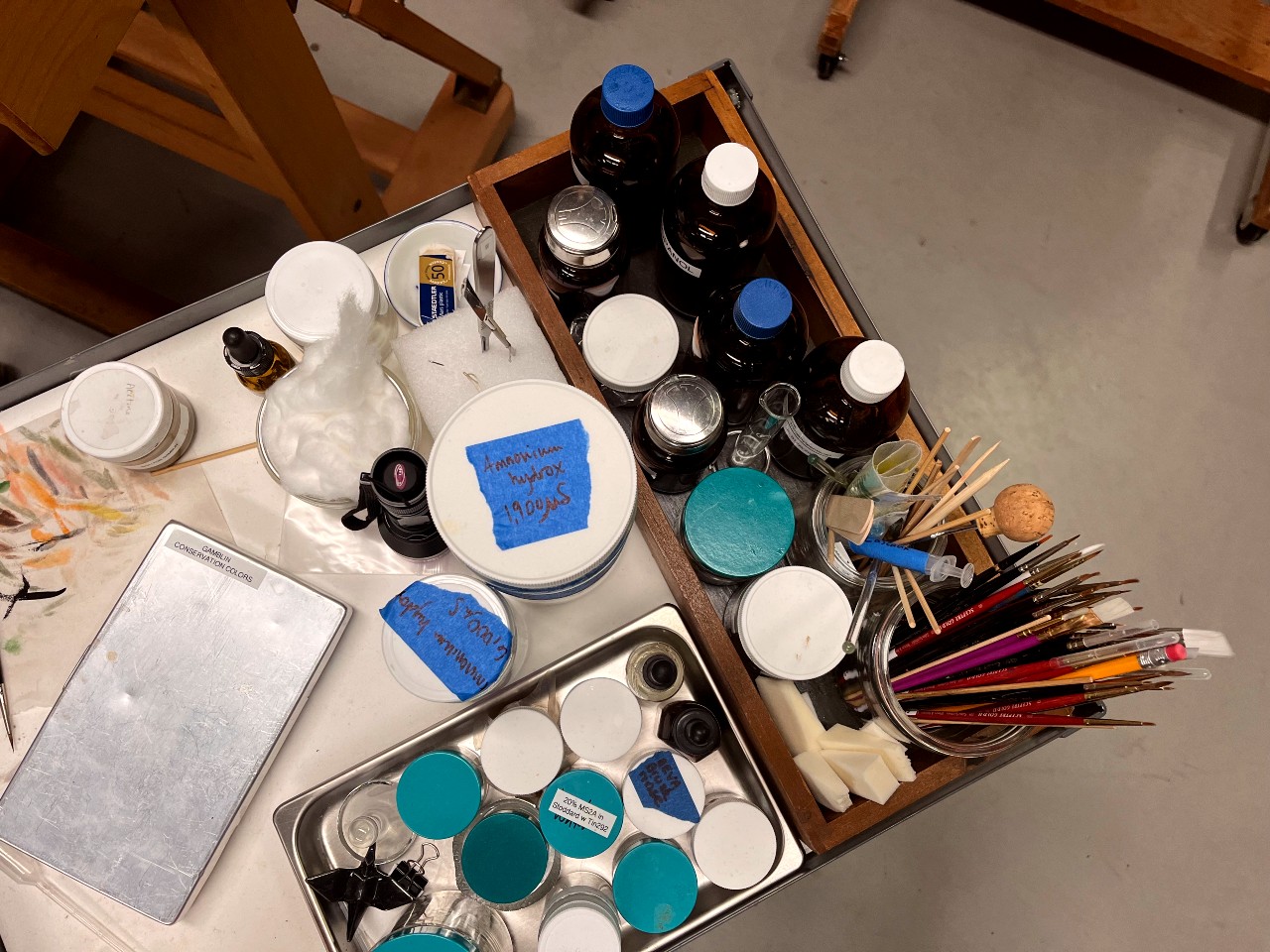

Conservators often work with chemicals like those pictured to preserve and restore art objects. (Photo: Corinne Segal)

Conservators often work with chemicals like those pictured to preserve and restore art objects. (Photo: Corinne Segal)

The most important, and often most difficult, question is about the artist themselves: What was the artist’s or maker’s intention, and are my interventions helping or potentially harming their work? Damien Hirst chose to use live blowflies, specifically highlighting their life cycle to comment on death as a part of life. Whether or not I liked the art, or found it successful, the art conservator’s goal is to make sure the art is the truest it can be, no matter where this leads.

Lisa Bruno is the Carol Lee Shen Chief Conservator at the Brooklyn Museum.