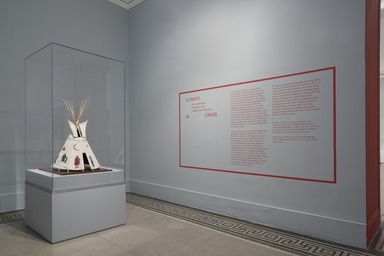

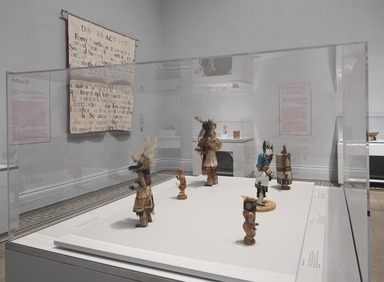

Climate in Crisis: Environmental Change in the Indigenous Americas, Friday, February 14, 2020 through Sunday, July 9, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Climate_in_Crisis_01_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Climate in Crisis: Environmental Change in the Indigenous Americas, Friday, February 14, 2020 through Sunday, July 9, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Climate_in_Crisis_02_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

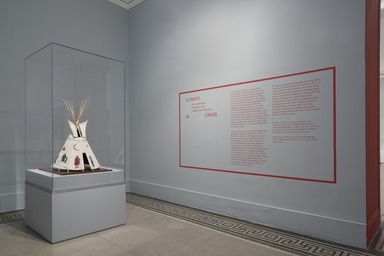

Climate in Crisis: Environmental Change in the Indigenous Americas, Friday, February 14, 2020 through Sunday, July 9, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Climate_in_Crisis_03_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

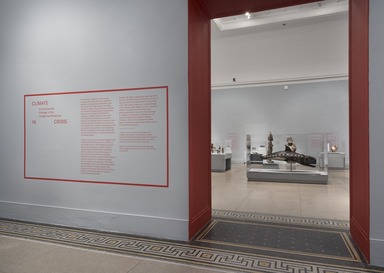

Climate in Crisis: Environmental Change in the Indigenous Americas, Friday, February 14, 2020 through Sunday, July 9, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Climate_in_Crisis_04_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Climate in Crisis: Environmental Change in the Indigenous Americas, Friday, February 14, 2020 through Sunday, July 9, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Climate_in_Crisis_05_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Climate in Crisis: Environmental Change in the Indigenous Americas, Friday, February 14, 2020 through Sunday, July 9, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Climate_in_Crisis_06_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Climate in Crisis: Environmental Change in the Indigenous Americas, Friday, February 14, 2020 through Sunday, July 9, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Climate_in_Crisis_07_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Climate in Crisis: Environmental Change in the Indigenous Americas, Friday, February 14, 2020 through Sunday, July 9, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Climate_in_Crisis_08_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Climate in Crisis: Environmental Change in the Indigenous Americas, Friday, February 14, 2020 through Sunday, July 9, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Climate_in_Crisis_09_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Climate in Crisis: Environmental Change in the Indigenous Americas

-

Climate in Crisis: Environmental Change in the Indigenous Americas

For millennia, Indigenous communities throughout the Americas have maintained profound and expansive relationships with the natural world. Beginning in the 1500s, however, Europe's conquest and colonization of the Americas forced ways of using natural resources that clashed with traditional Indigenous modes of relating to the world. This fundamental difference in worldview—between one that sees human beings and their surroundings and interrelated and another that emphasizes human needs at the expense of the environment—has resulted in ever-escalating threats to Indigenous homelands, ways of life, and survival as well as an unprecedented level of climate change.

Climate in Crisis: Environmental Change in the Indigenous Americas explores the effects of the climate crisis on both Indigenous communities and the planet as a whole. A central concept here is environmental colonialism, which considers the cumulative impact of land seizures, government and corporate development projects, and accelerated natural-resource extraction on Indigenous peoples over the past five hundred years. This history is manifested today in environmental problems such as wildfires, droughts, glacial melt, scarcity of resources, displacement of Native peoples, and violence against Indigenous communities and activists.

Divided into regional groupings spanning North, Central, and South America, the works of art on view connect to the environment in one of two ways: many reveal Indigenous understandings of the natural world as it relates to culture, spiritual beliefs, and daily life, while others more directly address the threat of climate change to Indigenous livelihoods. From the northern Arctic to the southern Amazon, Climate in Crisis demonstrates the central place of Indigenous worldviews in the creation of environmental justice. -

Canadian and U.S. Arctic

For the Inuit, ice is much more than frozen water; it is our highways, our training ground and our life-force. It’s something we thought to be as permanent as mountains and rivers in the south. But, in my generation, the Arctic sea ice and snow, upon which we Inuit have depended for millennia, are now diminishing.

—Sheila Watt-Cloutier, Inuit environmental and human-rights advocate, writer, and Nobel Peace Prize nominee, 2019

Indigenous peoples have lived throughout the North American Arctic region for approximately twelve thousand years. About forty Indigenous groups live in the Arctic today, each with unique histories, languages, and traditions. (The term “Eskimo,” while problematic because it masks this diversity, is used here when a specific group is unknown.) The nearby objects from present-day Canada and the United States reflect the common Indigenous understanding of the natural world as a foundation for culture, spiritual beliefs, and survival. Recurring imagery of animals and activities such as hunting and fishing underscores the relationship between traditional societies and the natural resources once abundant in the region.

In the 1700s, the introduction of commercial whaling by Dutch, Scottish, French, and U.S. crews severely impacted the Arctic ecosystem, followed just decades later by unsustainable hunting of caribou, musk ox, walrus, and other animals. Today, Arctic temperatures are rising twice as fast as the global average. In the past three decades alone, multiyear ice—ice that remains frozen through multiple melting seasons—has declined by 95 percent, shifting animals’ migration patterns, devastating the region’s biodiversity, and creating dangerous conditions that threaten the very existence of the ice and those who live on it. -

Canadian and U.S. Northwest Coast

As the salmon disappear, so do our cultures and treaty rights. We are at a crossroads and we are running out of time.

—Billy Frank Jr., Nisqually environmental and treaty-rights activist, 2012

Indigenous people of numerous tribal affiliations and nations have lived in the Northwest Coast region of North America, bordering the Pacific Ocean, since time immemorial, with ancestral homelands encompassing present-day British Columbia, in Canada, and Alaska, Washington, Oregon, and Northern California in the United States. Though diverse in their cultural and political identities, the tribes of the region share a reverence for the natural world, and family clans and belief systems are rooted in the environment and its life-giving resources. The diverse objects by Haida, Heiltsuk, Kwakwa̲ka̲’wakw, Tlingit, and Tsimshian artists displayed here depict similar motifs drawn from nature, such as the eagle, the raven, the orca, and the whale—a similarity that speaks to a common symbolism and understanding of the world across time and geography.

The land and waters of the Northwest Coast have been overexploited by non-Native people for the purposes of fishing, logging, mining, and agriculture since the early 1800s. Today, rapid environmental degradation continues as a result of population growth, pollution, adverse land-management policies, industrial-scale logging, and climate change, irreversibly impacting the natural resources of the region. Salmon, a cornerstone of many tribes’ cultural and economic sustainability, has experienced a significant decline in population over the past few decades. This shift undermines treaties that ensure Native people's right to fish, threatening tribal life as well as the integrity of the entire ecosystem. -

U.S. Mississippi River Valley

We are displaced. Our once large oak trees are now ghosts. The island that provided refuge and prosperity is now just a frail skeleton.

—Chantel Comardelle, Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Indigenous-rights advocate, 2018

While scientists agree that climate change is occurring today at an unprecedented rate, they also acknowledge its longer history across the planet. These objects illustrate an example of pre-Contact climate change, when the so-called Little Ice Age brought cooler temperatures and extreme weather to the Mississippi River valley. The Spiro Mounds archaeological site in present-day eastern Oklahoma was the western outpost of a series of prosperous cultures, referred to as Mississippian, that developed in the riverine regions of the Midwest and Southeast between 900 and 1650. In one of the mounds at Spiro, a hollow chamber was found containing thousands of ceremonial objects, including the engraved conch-shell cup on display, that had been brought there from all over the Mississippian world and from as far away as the Gulf of California and the Valley of Mexico. The ritual chamber and most of the offerings date to about 1400, when the Little Ice Age was causing disturbing environmental changes. Perhaps the offerings were an attempt to summon a new age of stability and abundance.

More recently, in 2016, the Isle de Jean Charles Band of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw became the first Native community to receive federal funding to support its resettlement as a result of climate change. Rising sea levels, land subsidence, and oil and gas development have forced the community from its homeland at the edge of the Mississippi delta and required that its members adapt their ways of life to a new region. -

U.S. Southwest

The Zuni people go to the Bears Ears area to pay respect to our ancestors in a way that is not very different from people going to a cemetery and paying respect to their family members. . . . The people that lived there and built the structures there and carved on the cliffs there, that created the ceramics and the baskets and other things that we see there—the blood of those people is in my veins.

—Jim Enote, Zuni tribal member and CEO, Colorado Plateau Foundation, 2018

The Hopi and Zuni are descended from the Ancestral Pueblo peoples, previously called the Anasazi, who lived for thousands of years in the region today divided among Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah. The Hopi refer to these ancestral lands as Hopituskwa (“Hopi land”), and the Zuni refer to them as Ulohnanne (“world” or “universe”), which encompasses land, water, subsurface, and sky. Both cultures rely on traditional knowledge and ecological rhythms to sustain farming techniques that are central to Native customs, rituals, and life. The kachina displayed nearby represent the spirits who bring rain and spur the growth of important crops such as corn.

The Hopi and Zuni count the Bears Ears region in southeastern Utah as part of their ancestral homelands (see nearby photograph). In 2016, President Barack Obama established the Bears Ears National Monument in recognition of the land’s “extraordinary archaeological and cultural record” and “profoundly sacred” meaning to many tribes. This monument status prohibits mining and other destructive activities such as looting and vandalism of the area’s roughly one hundred thousand archaeological sites.

In December 2017, President Donald Trump reduced the size of the monument by 85 percent in response to pressure from energy companies hoping to exploit its fossil-fuel and uranium deposits. The Hopi and Zuni, together with other tribes, filed a lawsuit arguing that the reduction is illegal. In September 2019, a federal judge ruled that the lawsuit could proceed, requiring in the meantime only that "timely notice" be issued before the federal government initiates potentially harmful activities on the no longer protected lands. -

Mexico and Guatemala

People say the climate movement started decades ago, but I see it as Indigenous people protecting Earth thousands of years ago. We need to bring [this philosophy] back and weave it into today’s society. People are here not to take over life, but to take care of it. It shouldn’t be "we the people." It should be "we the planet."

—Xiye Bastida, Otomi-Toltec climate-justice activist and Lead Organizer, Fridays for Future, 2019

Between about 1200 B.C.E. and the Spanish conquest in 1521 C.E., groups such as the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec established sophisticated civilizations with monumental art and architecture, large-scale farming, and complex calendars and writing systems. For three millennia, these Indigenous cultures residing primarily in present-day Mexico and Guatemala created a vast array of aesthetic, functional, and sacred objects. The range of approaches and techniques displayed here—including Olmec jade carvings and Aztec stone sculptures—testifies to the diversity of artistic expression in the region. Many of the forms and motifs demonstrate a close interplay between the spiritual and natural worlds, a view that, in general terms, continues to inform Indigenous practices in the area today.

In the five hundred years since Spain’s deadly conquest and occupation of Indigenous lands, the region’s climate and ecosystems have experienced significant changes that have destabilized and displaced Native populations. During the 1500s and 1600s increased fluctuations in temperature and rainfall disrupted agricultural traditions and Indigenous biodiversity, the effects of which continue to shape the natural environments of Mexico and Guatemala. Today, Indigenous activists in areas such as Mexico’s Sierra Madre are advocating for environmental reform and Indigenous land rights in an attempt to overcome the violent actions against people and the environment perpetrated by logging and mining profiteers. -

Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia

For us, territory is everything. It is life, water and food. It is where we pass on our culture and knowledge. It is where we practice our spirituality.

—Angelica Ortiz, Wayúu human-rights activist and General Secretary, Fuerza de Mujeres Wayúu, 2017

The objects in this part of the exhibition originated in present-day Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia. While they represent different cultures, all the works share a common belief in the connection between the natural and spiritual worlds. Representations of rulers, warriors, shamans, and supernatural beings incorporate attributes of animals that were revered for their strength and other natural abilities. Certain qualities of the materials also reinforce this connection to the natural world, whether it is the hardness of volcanic stone or the lustrous appearance of gold, which is associated with the sun and Native cosmologies.

While the thrust of urban development in Costa Rica, relative to other Central American countries, has been balanced by a concern for conservation and environmental sustainability, Indigenous people in Panama and Colombia have had to combat the spread of logging and other causes of deforestation, which are displacing communities from their ancestral homelands. In addition, the increasing frequency of hurricanes and other extreme-weather events threatens the well-being of Indigenous communities. Environmental activists from these regions—though dealing with different national and political circumstances—are speaking out against the impact of the climate crisis on their ways of life. -

Climate Change and Immigration

Our Mother Earth—militarized, fenced-in, poisoned, a place where basic rights are systematically violated—demands that we take action. Let’s build societies that are able to coexist in a dignified way, in a way that protects life.

—Berta Cáceres, Lenca environmental and human-rights activist, 2015

Although discussions of immigration usually focus on its economic and political dimensions, climate change is increasingly recognized as a significant factor in human displacement. As the climate crisis intensifies, migration escalates across the globe. It is estimated that by the year 2050, two hundred million climate refugees will have left their homelands in search of new places to live.

Encompassing Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, the “Northern Triangle” of Central America is one of the regions most vulnerable to climate change. In recent years, floods along the coastlines and droughts in the highlands have multiplied, affecting rural communities and their economies and forcing millions of people to immigrate either domestically or internationally. Often, these people become victims of political violence and social marginalization.

Furthermore, the migratory response to climate change in Central America is transforming an ancient relationship between people and the land. The difficulty of growing corn today, for example—a crop that has been cultivated in the region for millennia—has significant repercussions that are not only economic but also religious and cultural. -

Peru

Many communities already feel the effects [of climate change]—glaciers are reducing, in the Andes water is less accessible and we have to walk further to get it. . . . We used to [plant] next to the river, now we cannot. Our food security has already been impacted. For centuries our people have relied on Mother Nature to dictate when to plant and when to harvest, and now there is no regularity for us to rely on.

–Gladis Vila Pihue, Quechua environmental and human-rights activist and Women and Youth Programs Coordinator, Asociación de Productos Ecológicos, 2014

Approximately two thousand Indigenous tribes flourished along the Andes Mountains and the nearby coasts in the millennia prior to European colonization. The works shown here were made by artists from several different cultures that inhabited the area known today as Peru and demonstrate some of the ways those cultures reflected on and connected to the natural world. In Quechua, the most common ancestral language still spoken in the Americas today, the word pacha encompasses interrelated ideas of space, place, time, and the universe. This worldview continues to inform much Indigenous activism and advocacy for environmental stewardship.

Peru is an ecologically diverse country that includes mountainous highlands, an arid coastline, and vast tropical areas of the Amazon rain forest. The effects of climate change manifest themselves in myriad interconnected ways. For example, melting glaciers in the high Andes not only affect rainfall but also lead to an increase in floods and landslides toward the coast. The complex situation is exacerbated by companies’ attempts to seize land from farmers and herders to facilitate oil and gas extraction, gold mining, and illegal logging. However, in the face of these threats as well as proposed land developments, Indigenous resistance is managing to stall such projects and bring attention to their effects on Native people. -

Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru

When you destroy nature and foreclose the Indigenous peoples’ way of life, preventing them from exercising their culture, you are killing them. If we do not follow our culture, our tradition, we are no longer people.

—Sônia Guajajara, Guajajara environmental and Indigenous-rights activist and Executive Coordinator, Articulação dos Povos Indígenas do Brasil, 2019

Prior to European colonization in the 1500s, several million Indigenous people inhabited the Amazon rainforest, which spreads across a sizable area of South America, including parts of present-day Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. About two thousand different tribes once inhabited the ecologically diverse region within the current borders of Brazil alone, where only three hundred survive today. One such group, the Ka’apor, is best known for its brightly colored featherwork, a selection of which is displayed here.

Since the sixteenth century, the Ka’apor have been displaced from their homeland, in the northern state of Maranhão. Today, a large group of Ka’apor reside on an Indigenous reserve in the high Amazonian forest, where illegal mining, logging, and cattle ranching have devastated about one-third of the land since the late 1980s. In recent years, members of the Ka’apor have attempted to protect their territory through forceful confrontations with loggers.

Across the Amazon, which is the primary homeland of Indigenous communities in present-day Brazil, the ongoing effects of deforestation caused by commercial farming, ranching, and private industry have increased the frequency and destructiveness of wildfires. These fires threaten not only the environment but the very survival of Indigenous peoples.

![Kachina Doll (Angwusnasomtaqa [Crow Mother])](https://d1lfxha3ugu3d4.cloudfront.net/images/opencollection/objects/size0/2010.6.2_front_PS2.jpg)