African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_01_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_02_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_03_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_04_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_05_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_06_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_07_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_08_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_09_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_10_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_11_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_12_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_13_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_14_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_15_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations, February 14, 2020 through November 15, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Global_Conversations_16_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

African Arts—Global Conversations

-

African Arts—Global Conversations

African Arts—Global Conversations puts African arts where they rightfully belong: within the global art historical canon. Presenting African arts alongside non-African arts provides opportunities for greater, meaningful art historical conversations and permits critiques of previous ways that encyclopedic museums and the field of art history have or have not included them.

The exhibition’s unique transcultural approach pairs diverse African works with objects from other continents and cultures. Considering how similar themes and ideas developed independently in various parts of the globe, it offers new theoretical models for discussing African arts as equals with non-African ones. Moving beyond the older art historical narrative that European Modernists “discovered” African arts during the twentieth century, this exhibition begins the process of filling in the blanks in decades of art history textbooks and museum displays.

Installed throughout the museum, Global Conversations presents African artworks from a range of places, periods, and media in conversation with works from the collection that share similar themes, including faith, self-representation, history, portraiture, aesthetics, and style. A snapshot of the larger exhibition, the seven selections in this gallery re-present major art historical concepts and movements, recasting them with an eye toward the African continent. The conversation continues throughout the museum, with installations on additional floors.

This exhibition is the first of its kind to take a transcultural approach that connects diverse African works with objects made around the world, and the first to consider media beyond that of sculpture in a cross-cultural exhibition of this type. -

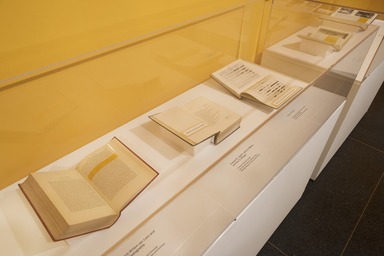

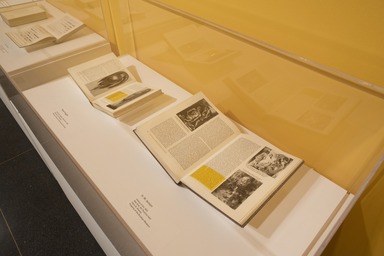

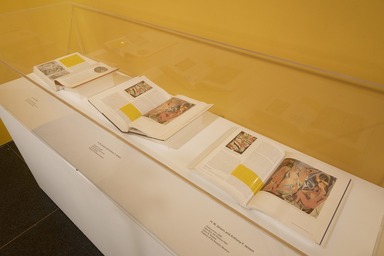

Writing the History of Art

These textbooks are representative of what many high school, college, and university instructors assign for introductory art history classes, and also are typical of art history books available at libraries and bookstores. Whether written in the 1930s or the 2000s, they have focused on European and American arts, with African arts overwhelmingly considered only in relation to European Modernists such as Pablo Picasso and Amedeo Modigliani. Some older textbooks did include short sections on African arts, in which the works presented often were labeled “primitive.” This pejorative term implied that the works lacked naturalism or realism, and that their makers were unevolved. “Primitive” was commonly applied to non-Western arts, though it sometimes was used for medieval or earlier European arts that used stylized forms. At the same time, textbooks such as A History of World Art (1940) omitted Africa altogether, as did History of Art (2001), published four decades later.

Textbook content is changing, however, as present-day art history courses globalize their curriculum by including non-Western art. There are now several textbooks dedicated solely to African arts. Despite this, only 6 percent of the content of Advanced Placement Art History (a college-level high school course) focuses on African creativity. Spanning some seven decades, the texts on view here reflect the types of sources from which many museum visitors learned art history. They also illustrate the necessity of centering African arts in conversation with works from around the globe. -

Creating Something New

All cultural practices, religions, and arts draw from precedent and from interactions with one another, but only some artworks contain recognizable components that make such connections clearer. Although art historians and museums have historically labeled this mixing as “hybrid” or “syncretic,” contemporary scholars increasingly believe that those two words imply an impossible cultural purity. Instead, they favor the term transcultural, suggesting that a work can transcend or bridge cultures. Paired here are two carvings with imagery drawn from several artistic contexts. One sacred and the other essentially secular, they were created millennia apart. Yet both convey the enduring human desire to create objects that feel at once new and familiar. -

Part and Whole: Architecture in the Museum

Whether functional, decorative, or both, architectural ornament helps convey something about a building and its intended inhabitants or users. Created by artists who may or may not have been well-known, these fragments were once part of greater cultural and architectural wholes. In a museum, we can only approximate the totality of a building, let alone the multi-sensory experience of its environment. Whether removed from their original settings because of changing tastes or weather damage, or by art collectors, the exterior building ornaments exhibited here have effectively become stand-alone sculptures. This transformation may or may not differ from how they were first understood by the societies of origin. This grouping allows us to consider both their initial contexts and their “second lives” in the museum. -

Iconoclasm

Iconoclasm is the rejection or destruction of beliefs, images, buildings, or monuments. It is typically used for religious or political reasons. While iconoclasm seems destructive, it can also be seen as constructive. Damaging all or only part of a work—particularly one tied to spiritual practices or a ruler—can deactivate its power. Depending on the circumstances, this deactivation can encourage the acceptance of new beliefs or leaders. Iconoclasm may also be an act of agency, preserving something from falling into the wrong hands by removing its essence. While their belief systems were different, both ancient Egyptians and nineteenth-century Kongo peoples believed that sculptures could host intangible things such as spirits or souls. Empowered or activated through ritual, iconoclasm was one way to deactivate these objects. These paired African sculptures consider how iconoclasm can be simultaneously destructive and constructive. -

Crossroads: Orthodox Ethiopia and Catholic Italy

Africans and Europeans had extensive contacts before the colonial eras, resulting in the exchange of art and ideas. Ethiopia and numerous Italian states, in particular, enjoyed a lively relationship in the medieval and early modern periods (the latter dating roughly from 1500 to 1800). Dozens of Ethiopians lived and worshiped at the church and monastery of Santo Stefano degli Abissini at the Vatican from at least the fifteenth to the eighteenth century. Ambassadors from the Christian Ethiopian kingdom traveled to Italy, while those from Venice (and other European powers) went to Ethiopia, all bringing religious art with them. This grouping of processional crosses considers the Christian connections these regions shared. -

Reassessing European Modernism and “Africa”

All artists draw from sources both within and outside their culture. The so-called discovery of African arts and subsequent borrowing and stereotyping of their sophisticated aesthetics by Picasso and other European Modernists has dominated the Western writing of art histories, as the textbooks on view in this exhibition’s first-floor gallery show. Notably, however, what art historians have defined as European Modernism overlaps with a peak period of European imperialism, requiring us to ask why certain African arts became available to European artists. But Africa is not a country, and there is no such thing as a monolithic “African art.” Furthermore, African artists are just as modern as their European counterparts. They respond to the cultural, social, and stylistic concerns of their times, drawing from or breaking with traditions in all their variations. This pairing considers a Fang artist’s mask alongside a Picasso portrait to illuminate links between colonialism, art collecting, and artistic imagination, as well as to consider two artist’s distinct approaches to depicting women. -

Might and Memory

Warriors hold a valued place in many societies across time and place. They can uphold laws, protect values, or act as agents of change and conquest. Their violence inspires both fear and admiration, as does their sacrifice. Frequently, they are associated with ancestors or gods, from whom they may draw strength or inspiration. Memorials for warriors reflect a society’s image of what these figures “should” look like, often representing ideals rather than individuals. Their group membership dominates representations of them, reflected by the “typical” symbols they wear. This trio considers how two distinct societies memorialize warriors and the people connected to them. -

Idealized Portraits

Artists tread carefully when depicting rulers. They must make their subjects recognizable and, often, flatter them. The resulting images should respect cultural norms about how a ruler is expected to look or dress. Around the world, idealized portraits of rulers meet these requirements by combining individualized features with generalized traits. Sometimes they depict concepts, such as divinity or rulership itself. This grouping pairs two idealized portraits from disparate times and places in Africa: ancient Egypt and the eighteenth-century Kuba kingdom. Historically, museums and art historians rarely paired pharaonic Egyptian and sub-Saharan African arts. This was because nineteenth-century Western scholarship artificially separated the continent along racist lines, promoting the false idea that it was divided into differently evolved “Black” and “Arab” sections. While recent Brooklyn Museum galleries rightly acknowledge the connections between these regions, many textbooks are still catching up. -

Feminisms

The term feminism is best understood in the plural: feminisms. The priorities of Second Wave feminism in the West as it emerged in the 1960s and '70s were primarily driven by educated white women. Women of color found communities with common interests that were largely not addressed by Second Wave feminists. Since the 1980s, international voices have expanded the conversation. Today, intersectional feminisms prioritize how race, class, ethnicity, religion, and ability alter the experience of gender, and also challenge the historical binary understanding of gender. These paired works illustrate how two artists working more than forty years apart—one Nigerian and the other American—use collage to focus attention on those that conventional art historical and social narratives left out. Each defines “feminism” in relation to her home country and personal experiences. -

Souvenirs as Self-Representation

A souvenir is a tangible reminder of a place visited, a memento from a past experience, or a way to show others where you have been. For their makers, they bring up an important question: how do you represent yourself and your community to others? Museums and art historians have historically dismissed souvenirs as inauthentic or low-quality objects made for sale to outsiders. African works placed in this category have been particularly denigrated, although high-quality souvenirs from the continent have existed since the fifteenth century. While most contemporary mass-produced trinkets lack artistic merit, historic mementos can reveal cultural meaning. This grouping assembles three works that demonstrate how souvenirs express cultural self-representation, capturing the values and details of an era. -

Multiple Modernities

As the nearby art history textbooks published in America illustrate, past scholarly ways of looking at modernism in the Western context have been linear and Eurocentric. As a result, African artists were often left out of modernism’s story, or even disparaged for producing work deemed “derivative.” From the mid-1990s, new scholarship has reflected the concept of “multiple modernities.” The theory argues that different cultural narratives result in different kinds of modern art, all equally modernist and connected in complex ways. Museums and academic institutions are still catching up to this approach in their teachings, collections, and exhibitions. This pairing considers how two artists—one Ghanaian, one American—used abstraction to create distinctive modernisms. -

Ceramics: New Perspectives on Old Forms

Living artists made these three vessels. Yet the Brooklyn Museum has never exhibited them in contemporary art exhibitions or galleries. The birthplaces of their makers—Seoul, Nairobi, and Lagos—have, until now, been used as the primary organizing methods that dictate how museums have acquired, shown, and described their works. But these objects defy simplistic readings as “African” or “Asian.” Though each of their makers draws some inspiration from their individual heritage, none are limited by it. All have traveled and studied widely. Some have expatriated or live between different countries. Their influences bridge space and time, challenging definitions of what art from certain places “should” look like. This grouping of vessels exemplifies the global inspirations of three leading ceramicists. -

African Arts and the Harlem Renaissance

In the first half of the twentieth century, many African-American and European Modernists drew formal inspiration from the works of African artists. Although they shared resources, contacts, and intellectual concerns, their resulting works and connections to the continent differed. This grouping considers how Fang sculpture and other African arts inspired the New York-based African-American painter Beauford Delaney during the 1940s. It also reflects how artists and intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance (a dynamic intellectual, artistic, political, and socio-cultural movement that emerged in Harlem in the 1920 and 1930s) both drew on and diverged from European perspectives on African arts. -

Imagining Origins

How do societies imagine what their founders looked like? How do they pass that image on to future generations? Artist-made images play a crucial role in answering those questions, especially before the mid-nineteenth century invention of photography. Balancing observation and imagination with cultural values, portraits of founders represent more than an individual. They express the idea of genesis, the seeking out and recording of origins, and the human need to pass these stories on. This pairing of an equally iconic Kuba mask with an American portrait demonstrates how two artists represented their founding fathers.

-

December 10, 2019

This exhibition presents diverse African works throughout the Museum’s vast collections, putting African arts in its rightful place within the global art historical canon

African Arts―Global Conversations draws from the Brooklyn Museum’s extensive and renowned collections to assert the importance of African arts within the art historical canon. Spanning the entire Museum, the exhibition questions dominant narratives from Western art history and museum practices that have traditionally sidelined African arts, and makes important connections between the continent’s various artistic practices and those of other global cultural groups. Included in the exhibition are African artworks from a wide range of places and time periods, spanning circa 2300 B.C.E. to the present day, in conversation with collection objects from outside of Africa that share similar themes—from faith, race, and history to design, aesthetics, and style. For example, a Kuba artist’s mask of Wóót is shown alongside Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of George Washington in the Luce Center for American Art, illustrating strategies artists used to represent community founders and origins. By considering the independent development of shared themes and ideas from different parts of the world, African Arts―Global Conversations uses a uniquely transcultural approach to reconsider African art’s relation to art from other regions, moving beyond the narrative that African arts were “discovered” by European modernists.

The exhibition starts with an introductory gallery adjacent to the Museum’s lobby and continues throughout the Museum with groupings of works installed in galleries dedicated to collections for European Art, Arts of the Americas, American Art, Ancient Egyptian Art, and Arts of Asia. The introductory gallery includes examples of historical art history textbooks, illustrating the limited ways in which African arts have been included in the art historical canon, often appearing only as footnotes to European modernism. A snapshot of the larger exhibition, the seven groupings in the introductory gallery (including themes such as Feminisms, Multiple Modernisms, and Idealized Portraits) present major concepts and movements in art history, recasting them with an eye toward the African continent. African Arts―Global Conversations continues in other galleries in the Museum, exploring additional topics that include Crossroads: Orthodox Ethiopia and Catholic Italy, which pairs processional crosses from each kingdom, illustrating their historical connections and how the interpretation of the cross form varied across cultures; Might and Memory, which explores different expressions of power by contrasting sculptures dedicated to warriors from Ethiopia’s Konso peoples with those from the Huastec peoples of modern day Mexico; and Iconoclasm, which considers, through the pairing of a pharaonic Egyptian portrait sculpture and a Kongo power figure (nkisi), how acts of destruction can also be acts of agency. Also included in the exhibition is a mask carved by a Fang artist paired with a portrait by Pablo Picasso, reassessing the Spanish artist’s long relationship with African art and exploring his limited understanding of the continent’s diverse artistic styles, while also presenting each artist’s differing approach to images of women. American painter Beauford Delaney’s engagement with Fang sculpture is considered as well, in the grouping African Arts and the Harlem Renaissance, which includes vintage books by Alain Locke and Carl Einstein.

The exhibition includes thirty-three artworks, highlighting several new acquisitions and never-before-exhibited works, among others. Of the twenty artworks by African artists, important objects include a celebrated eighteenth-century Kuba sculpture of a ruler that is the only one of its kind in the United States, fourteenth- to sixteenth-century Ethiopian Orthodox processional crosses, and a mid-twentieth-century Sierra Leonean Ordehlay or Jollay society mask. Also featured are paintings, ceramics, and collages by contemporary artists Atta Kwami, Ranti Bam, Magdalene Odundo OBE, and Taiye Idahor. African works in the exhibition are paired with works by Māori, Seminole, Spanish, American, Huastec, and Korean artists.

“Art has many histories, and the story of art cannot be told without Africa,” said curator Kristen Windmuller-Luna. “There are more stories to tell about Africa’s role in art history than about one-sided influence, and this exhibition seeks to reassert Africa’s role in the narrative of art history. In today’s world, it’s crucial to promote a global understanding of art, one in which African arts—and other arts too often left out of the canon—are celebrated and included in the conversation.”

The Brooklyn Museum has one of the country’s largest and most important collections of African art and was the first museum in the United States to display African objects as works of art, in a landmark 1923 exhibition that explored the formal and aesthetic qualities of these objects for the first time. In anticipation of a thoughtful and dynamic future reinstallation of the Museum’s collection galleries for African arts, African Arts―Global Conversations is developed as one of a series of temporary exhibitions that seek to consider, display, and research the collection in new ways. With provenance labels for every work (both African and non-African), the exhibition also gives the Museum an opportunity to engage in deeper provenance research across the collection, allowing visitors to consider each object’s historical purpose as well as the individual path it took to enter the Museum’s collection.

African Arts―Global Conversations

View Original